Verdad Magazine Volume 16

Spring 2014, Volume 16

Verdad Interview with Poet Dana Roeser by Don Illich

Don Illich: "No poet I can think of writes better about the anxiety that fuels modern life.”—Elizabeth Spires

How did the anxiety of modern life become one of your subjects? How does it fuel your writing?

Dana Roeser: I am a student not only of anxiety but of how to break it up, interrupt it. I use surprise (e.g., abrupt changes in syntax—sudden stops, pivots, exclamations, etc.), disparate associations, sudden switches in subject matter, humor (which can be a part of the preceding), the lyric moment and/or epiphany (I hesitate to use that word), and so on. Anxiety does fuel my writing, but so does the earnest desire to not let it get a stranglehold on my work or my life.

DI: "A lyric poet who writes narrative poems, Dana Roeser is a poet who transcends classification.”—David Dodd Lee

How do you manage to write poems that are both narrative and lyric? How does it serve your subject matter?

DR: I appreciate David Dodd Lee saying that my poems are both narrative and lyric. I am striving for a balance of poetic elements. I do love stories, both to tell them and to hear them. I think parts of stories or small stories made large and large ones “excerpted” are very thrilling as vibrant bits/strands in a poem. (I rarely read a novel all the way through. The second half is sometimes a disappointment!) What interests me is delivering a quick sketch of a character often through his/her voice.

I’m sure it sounds disingenuous, but I do not consider subject matter to be primary in my poems. I wasn’t able to write poems until I made it secondary to the shape and other prerogatives of the poem. Subject is a material like oil paint, color, dried pasta, clay, marble--and so are image, diction, voice, syntax, sound, etc., to name a few.

In other words I let the form determine the subject matter. I start with certain images that begin to constellate, but the poem pretty much depends on voice, which is established at the outset. I aspire to be like a percussionist friend of mine, Don Nichols, who uses “real-time electronics and a wide range of percussion instruments, which include pitched and un-pitched . . . , traditional and non-traditional drum sets, resonant metals and gongs, hand percussion and found objects” in his exciting compositions.

DI: Claudia Emerson said your poems "are concerned finally with ‘the corporeal self’." How important is the corporeal self, the body and its vulnerabilities, to your work?

DR: It is important, insofar as the body’s frailties make us (and others) vulnerable to death and injury. This is the human condition. The body is like the dwarf’s treasure that he hauls around the forest in fairy tales, burdened by its weight and sometimes wanting to hide it somewhere so he can keep it without carrying it. We hoard our bodies, as we hoard material possessions, and other signifiers of our security. It’s pointless, but we cling anyhow.

DI: You're known for your "quirky, syncopated short lines."

How did you develop that style, and how does it affect what you write about?

DR: I developed this style, because in 1994 Richard Howard told me that my lines were dead. I cut the line off midstream while it was still lively and interesting. An ancillary benefit is that whatever narrative is unfolding speeds up because of the asyntactical breaks. The short lines serve my subject matter and desire to mix several elements. In this form everything is foregrounded and nothing is made subordinate. There is no finding a “topic sentence” in such a form. Also, the short lines emphasize changes in voice, pivots, stops, exclamations. A pleasing disorientation can result. I like the clashing collage effect.

DI: Who are the poets who were and are important to you in your writing and development? In what way did they influence you?

DR: Frank Bidart—voice and fearlessness

James Schuyler—voice and line, hilarity

Anne Carson—“fictionalizing” and shaping raw material; the use of hybrid forms

Matthew Dickman—verve

William Carlos Williams—the variable foot

Tony Hoagland—humor, expanding the sense of what can be put in a poem

Bob Hicok—ability to morph from poem to poem, book to book

Laura Kasischke—fantastically associative

Albert Goldbath—a goldmine

Mark Halliday—brilliant stand-up comic

Emily Dickinson—large capacity for ecstasy

Shakespeare—“spirits to enforce, art to enchant”

Robert Lowell—“the grace of accuracy”

Vallejo—his duende

Neruda—his colors; generosity of spirit

Charles Wright—interchangeability of surface and depth

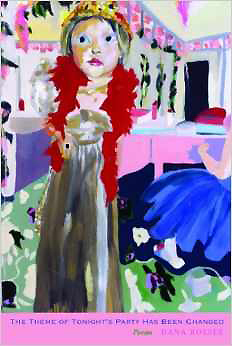

DI: What would you like to say about your most recent book, "The Theme of Tonight's Party Has Been Changed"?

How is it different from your previous works?

DR: I think Elizabeth Spires says it well: “The pleasure in reading these poems may be in the way they both amuse and alarm as they capture the texture and split focus of contemporary experience where two, three, or four things must be held in the mind simultaneously, often at the poet’s peril.”

As various friends and “frenemies” have noted, this is a dark book. But it should be taken as Kafka and Max Brod took Kafka’s stories and novels: when Kafka read them out loud to Brod in his apartment in Prague, they laughed uproariously. The book should be read, partly, as a study in black humor. If you don’t smile over lines like “It was a bad/day we didn’t/know why/we hated ourselves,” you might want to wait for the next book—which will be full of joy, laughter, tornadoes, and horses.

Dana Roeser's poem Be Where Your Hands Are is in Verdad's current issue.

About the poet's work: Acclaimed poet Tony Hoagland says that “Dana Roeser’s lanky poems are neck-deep in life, and relentlessly intent on learning the truth. She has her own charming and muscular prosody; she tells lively, moving stories; but it is the determined persistence of their very human speaker which drives the poems.” Rodney Jones, recent winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Prize, says that her “overarching theme is individual, feminist, contemporary: how does a woman know herself apart from convention and duty?” Dana Roeser delivers to us a world filled with cars breaking down, young children throwing up, a mother dying, women in their underwire bras getting struck by lightning—all the usual, casual, catastrophic events of our lives folded together with other foreign objects into a child’s crazy King Cake.

BIO: Dana Roeser is the author of three books of poetry: Beautiful Motion (2004) and In the Truth Room (2008), both winners of the Samuel French Morse Prize, and The Theme of Tonight’s Party Has Been Changed, winner of the Juniper Prize (University of Massachusetts Press, March 2014). This most recent book was recognized by Library Journal as one of “Thirty Amazing Poetry Titles for Spring 2014.”

She has been the recipient of an NEA fellowship, the Great Lakes Colleges Association New Writers Award, and the Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Washington Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in The Iowa Review, Harvard Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Antioch Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Laurel Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Massachusetts Review, Prairie Schooner, Southern Review, Northwest Review, POOL, Shenandoah, Sou’wester, and other journals, as well as on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily.

Roeser has received fellowships for residencies at Yaddo, Ragdale, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Le Moulin à Nef (VCCA France), St. James Cavalier Centre for Creativity (Valletta, Malta) (VCCA International Exchange), and Mary Anderson Center for the Arts.

Dana Roeser's website: www.danaroeser.com/

The Theme of Tonight's Party Has Been Changed: Poems (Winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry) Paperback – Univ. of Massachusetts Press (March 31, 2014)

The Theme of Tonight's Party Has Been Changed: Poems (Winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry) Paperback – Univ. of Massachusetts Press (March 31, 2014) "Sui generis, Dana Roeser's poems are spoken by a stand-up comic having a bad night at the local club. The long extended syntax, spread over her quirky, syncopated short lines, contains (barely) the speaker’s anxieties over an aging father with Parkinson’s, the maturation of two daughters, friends at twelve-step meetings and their sometimes suicidal urges—acted on or resisted—and her own place in a world that seems about to spin out of control. Bad weather and tiny economy cars speeding down the interstate next to Jurassic semis become the metaphor, or figurative vehicle, for this poet’s sense of her own precariousness."

Roeser brings a host of characters into her poems—a Catholic priest raging against the commercialism of Mother’s Day, the injured tennis player James Blake, a man struck by lightning, drunk partygoers, an ex-marine, Sylvia Plath’s son Nicholas Hughes, a neighbor, travelers encountered in airport terminals, various talk therapists—and lets them speak. She records with high fidelity the nuances of our ordinary exigencies so that the poems become extraordinary arias sung by a husky-voiced diva with coloratura phrasing to die for, "the dark notes" that Lorca famously called the duende. The book is infused with the energy of misfortune, accident, coincidence, luck, grace, panic, hilarity. The characters and narrator, in extremis, speak their truths urgently."