Verdad Magazine Volume 31

Fall 2021, Volume 31

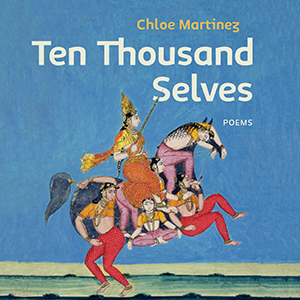

Ten Thousand Selves by Chloe Martinez

The Word Works Press, 2021Review by Bill Neumire

In conversation with eastern philosophy and the Taoist idea of the ten thousand things, Chloe Martinez’s Ten Thousand Selves reminds us, as she put it recently in a Kenyon Review interview, “we are all messier and more multiple than we often acknowledge.” A scholar of South Asian religions, she develops this discussion of the selves in a book that turns to the motif of the mandala--sacred geometric figures that often represent a spiritual journey through layers--to describe the speaker’s selves: teenaged selves, professional selves, female selves, mother selves. It’s a book that uses the self in all its iterations as a necessary lens to engage art, travel, and relationships. In a proem called ‘The Mirror Room,’ the speaker recounts her experience at the Sheesh Mahal:

Sheesh Mahal means Mirror Palace, or else

Hall of Mirrors, but it is just a tiny space, dim, claustrophobic

with reflections: wild, intimate room, it wants an audience.

Here you are, alone with your ten thousand selves.

This begins a motif of mirrors, introspection, solitude--an exploration of the way a lived life is a palimpsest of previous selves, as well as a kaleidoscope of current selves divided over experiences with others. It is a journey of understanding couched in the terms of religious struggle:

There will be no battle against the senses,

no progress from the simple periphery to the inner circle,which contains, in some traditions, the most fearful opponents,

some dangerously beautiful, others just plain dangerous.

The speaker comments on the iterations of her life and travels--when she was a teen, a young mother, a working professional--and often the divide of selves is quite explicit, as in the poem titled ‘Four Past Selves as I Recall Them’ (Thief, Ant-Killer, River Reed, Mirror). In another poem about a baby grand piano the speaker says, “On my 41st birthday, / a dark wooden curved piece of the nineteenth century,” ringing the notion of a history carried forward through an instrument that works via vibration and echo. Other I’s permeate the pages, and the speaker’s human/humane self is often at odds with her professional, employed self, as in ‘The Movement’:

Don’t

cry: you are at your place of employment.

Make your way to privacy. Because you are

human, only there may you be moved.

“How tiring the past is,” she announces, but the past is streaked with traces, and these selves are at once judgmentally compared and contrasted with selfies, glints of self, posed manipulations:

Don’t be that asshole over there

with her hippie hair; climbing on roots

two thousand years old, trying to get a better self-

ie

The speaker reaches back to her familial history to tell us that her “father, fathered by a cloud, became / a painter, someone who could turn anything beautiful.” This leads to one of the book’s revelatory questions: “Families gather around something, telling stories. What is there / at the center?”. It’s a moment that gives way to a desire to offer others another context: “Ancestor. I want to imagine you another life.” The self exists as maze, struggle, perilous journey: “Magicked, you lose missives / through the hedges of yourself: amazed, a maze.” It is connected to godhood, religion, and motherhood, as in ‘The First Person’:

You know someone already inside of whom is another

someone, scheduled to emerge in mere months, and by then

you will have made and discarded multitudes,

their eyelashes and bellybuttons appearing, disappearing

The interlocutor you is frequently the speaker’s baby, and the stance is often parental, wishing warning and wisdom: “My breasts ache anyway, still trained to / produce for you, and still, there is nothing better than your anger / silenced by your hunger.” One poem talks of being drugged at grad party; another is titled ‘After morning drop-off I change the station from kiss-fm to the Kavanaugh hearings,’ wherein she worries:

Maybe I should tell her

now, before she’ll need to know, how to fend off

the world, I mean eyes I mean words I mean

hands on her

There’s a pushback against an anti-woman capitalism perhaps captured best in ‘The God Structure,’ a poem about a customer review of the uniqlo beauty light bra: “It seems the God structure (...) / has written us this script. We read it aloud. We hope to resist a long time.” This even as Martinez’s speaker quips, “Skinny girls: selfie, selfie, text.” The self at large may be at odds with the selfie, but the selfie, the moment of passing reality, is an apt recognition of the ten thousand selves. This layered experience of selves that deal with the male world and gaze, gets heavy:

Oh, but one gets

exhausted, body

and soul, and whose hands

aren’t tired of being

reasonable

The poems are usually located, in their epigraphs, in a particular place, from Indonesian cities to New Bedford, Massachusetts. Dovetailing the motif of travel, Martinez often makes use of references to plants and animals as touchstones: fish, ants, Indra Swallowtail, seal, dog, lion. She turns to rare animals as moments of witness, as when speaking of two white wolves: “I am eight, watching them, // and nineteen, and forty” and we get to see different aged selves connect on the same archetypal vision of the wolf.

This book of ten thousand selves is a book that honors the places to which it travels, the selves to which it reaches out. The ten thousand selves are more than poses; they are the identities the speaker has carved out as experience, audience, maturity and relationship have dictated. And the perspectives these selves have formed allow her the optimism to hope, “we all // catch a little free beauty sometimes” and to assure the reader, who inevitably also carries ten thousand selves, that they “might just be the person to give [themselves] / advice on how to live.”

About Chloe Martinez

Chloe Martinez is a poet and a scholar of South Asian religions. She is the author of the collection Ten Thousand Selves (The Word Works) and the chapbook Corner Shrine (Backbone Press). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in AGNI, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah and elsewhere. She works at Claremont McKenna College. See more at www.chloeAVmartinez.com.

Ten Thousand Selves by Chloe Martinez

published by Word Works; (March 15, 2017)

ISBN-10 : 1944585079

ISBN-13 : 978-1944585075