Verdad Magazine Volume 7

Fall 2009, Volume 7

An Interview with Poet and Novelist Frank X. Gaspar

by Eric Loya

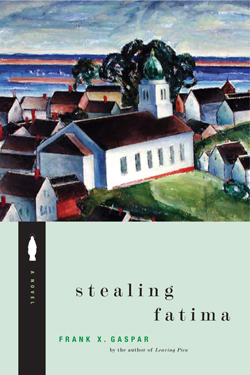

EL: Youíve just finished a new novel, Stealing Fatima. Whatís the premise? Is there any connection to your first novel, Leaving Pico?

Frank Gaspar: Stealing Fatima is set in the same mythical Provincetown, a Portuguese-American fishing village, art colony, and vacation spot. The time, however, is more nearly contemporary as opposed to Leaving Pico, which was set fuzzily during the late Eisenhower years. Stealing Fatima unfolds during a fuzzy time as well, but rather than cite a president, Iíd say more toward the end of the reign of Pope John Paul the second. Readers of Leaving Pico will spot a few familiar names and places, but itís hardly a sequel. A junkie priest confronts a host of mysteries. They are in some ways everyoneís mysteries, but Provincetown is a very particular place, and the Portuguese and gay communities there are very particular communities. Everything gets a little crazy. If you look at the bookís Epigraphs youíll see that I wanted Nathaniel Hawthorne to meet Jose Saramago.

Frank Gaspar: Stealing Fatima is set in the same mythical Provincetown, a Portuguese-American fishing village, art colony, and vacation spot. The time, however, is more nearly contemporary as opposed to Leaving Pico, which was set fuzzily during the late Eisenhower years. Stealing Fatima unfolds during a fuzzy time as well, but rather than cite a president, Iíd say more toward the end of the reign of Pope John Paul the second. Readers of Leaving Pico will spot a few familiar names and places, but itís hardly a sequel. A junkie priest confronts a host of mysteries. They are in some ways everyoneís mysteries, but Provincetown is a very particular place, and the Portuguese and gay communities there are very particular communities. Everything gets a little crazy. If you look at the bookís Epigraphs youíll see that I wanted Nathaniel Hawthorne to meet Jose Saramago.

EL: What are the differences between writing a first novel and a second?

FG: Yes, there were great differences in the actual writing of Leaving Pico and Stealing Fatima. Iím not sure I can say what they are! Leaving Pico was laboriously designed with an inset story intended to link the present-day Portuguese-Americans of this small town with the glory days of the Portuguese explorations of the fifteenth century. I find the book funny. I mean Columbus and Vasco da Gama wind up as rivals on the same ship. A boyís grandfather takes a few scraps of history and adventure novels and concocts a completely plausible Portuguese hero, the familyís direct ancestor (making the Carvalhos the princes of America!) who beats Columbus to the new world by a year. There is turmoil and heartbreak in the poor family of course, and itís woven together in parallel worlds, so to speak. Some people, however, read it as a simple coming of age novelóor quasi autobiography, though itís neither. It was very hard to write. It took years, literally, to find the voice and point of view, and to finesse the inset story. Okay, so Stealing Fatima was very hard to write and it took years, literally, to find the voice and point of view. But by this time I had learned some mechanical tricks. Like using different colored paper for different drafts, keeping an organized process notebookójust little things like that. I hit a slough after the first year or so and turned to poems, writing what became Night of a Thousand Blossoms. Then I put myself back to work and stayed away from poems, which was hard for me, and kept at the novel. I donít know where any of these characters came from. The early drafts were so very different. A ghostly Gerard Manley Hopkins was there at first! Once the Virgin Mary peeked in, she seemed to be everywhere (sort of) and there was no getting her back out. There were some hard times through that, but I wrote daily through most of them. The book went through great changes. Huge character shifts, strange plot twists. Itís a dark book that is full of (I hope) light. It exhausted me. Iím still tired from it.

EL: Besides enjoyment, what do you hope the readers take with them from Stealing Fatima? What do you want leave the reader with?

FG: Questions. What really happened? How do all these conflicting (and conflicted) wills add up? What is ďmiraculousĒ in the age of sub-atomic particles? What is possible to know? How does Provincetown (well, the mythical town in the book) keep reinventing itself into something so utterly crazy and wonderful, no matter what forces act upon it. Itíd be great if one reader somewhere lays Stealing Fatima down after the final sentence and feels like he or she has read a poem.

EL: Who do you read? Who influences your work?

FG: Well, that's a big, wonderful question. I can't think of many books I've read that haven't in some way shown me something. Sometimes you find something marvelous and life-changing, and you write toward that. Sometimes you find something dreadful or merely over praised, and you write away from that. It all seems like a great conversation to me, all the voices and worlds colliding in the big world of literature. I have old favorites that I revisit: Dickens, Dickinson, Pessoa, Rilke, Conrad, Melville, Hart Crane, Tennessee Williams, Jane Austin. Some contemporary novelists that I greatly admire are Kent Haruf, Mary Gordon, Alice McDermott, Cormac Macarthy, Shirley Hazzard, and John McGahern. In five minutes I would give you an entirely different list. I try to read everything.

EL: Do you have advice for emerging writers?

FG: Write every day and read every day. Think of yourself as a professional. Let all your other activities revolve around reading and writing. Read everythingónovels, stories, plays, poems, theory, criticism. If this is hard for you to do, then it might mean that the writing life is not for you. If you love this sort of thing, then it doesnít seem like work. Or it seems like work of the highest possible calling.

EL: What should students look for in a writing program?

FG: Writing programs arenít magic. They canít turn you into a writer. Only you can do that. But that being said, programs are important in getting you around people who actually write and publish. You get to absorb what they do and how they stand in the world, and you can use this as a measure of your own stance. Of course you learn technique, and you workshop your poems and chapters with your peers, and that is a valuable experience. You develop community. You find out whose advice to trust. We are lucky here in the L.A. area with so many fine programs, both traditional and low-residency. And Long Beach City College has been a place where anyone could come and build his or her skills for transfer to a university, for grad school, or for personal growth. I think the two things I came away with from my writing program (U.C. Irvine) were, first, to read every day professionally: poetry, criticism, novelsóeverything, across all time periods and cultures. The second was to write every day professionally no matter what else was going on in my life. These are ideals, of course, but ideals that are within everybodyís reach if they are serious. In a sense you have to create yourself as a writer, and writing programs can give you a strong start in doing that.

EL: Whatís your process? What happens when you write?

FG: I read and write all the time. I have regular habits and schedules, and against those I play irregular habits and anti-schedules. I have a room that I like to call my studio in my more obnoxious moments. Itís full of books and papers and the tools for writing. I write in notebooks and on computersóand every once in a while on one of the old typewriters I have sitting around the house, just to hear that rhapsodic clack, clack, clack of the steel keys. Sometimes when I write I am in a trance-like state (as I often am when I am in the grocery store or taking out the trash, so itís not a big deal). Sometimes my head is firing like lightning bugs and things get all fused together. Itís all fun, even the hard rewriting, in its fashion.

EL: Much of your previous work seems to have been influenced by Provincetown, where you were born, and the Portuguese community there. How does this continue to influence you?

FG: Isnít there an old saying, ďYou can take the boy out of the town, but you canít take the town out of the boyĒ? I think thatís how it goes. Provincetown was a magnificent, magical place to grow up in, and its geography is the contour of my psyche. I didnít choose it. It just is. I donít mean to imply that I was always happy there. There was a very dark side to my growing up there too. But I think having artists and writers all around, and being part of a very reclusive yet exuberant ethnic group were both important in making me whatever strange creature that I am. Iíll always see the world through the eyes of that skinny, dazzled kid that I was. I seem to be able to live with that.

EL: Iíve heard you speak about becoming the writer that writes the poem or novel you want to write. Could you expand on that? What does one do to become that writer?

FG: My wise-guy answer to that is always, ďmove your feet.Ē I first heard that idea of becoming the writer who writes the work from Stanley Kunitz. He talked about swimming away from overturned boats. You have to keep growing and changing, and this most of the time means through an act of will. If you donít have the tools to make the poem or novel you want to make, then you must acquire them. If you donít have the muscle you must build it. If you donít have the will, you must will yourself to become a person that has that will. When I start speaking sentences like that last one, I know Iíve said enough.

EL: Youíve quoted the Ginsberg line, ďwrite your mind,Ē many times in class. Is writing your mind a result of ďbecoming the writerĒ or does one have to write his/her mind in order to become the writer they want to be? Perhaps both?

FG: Hmm. Maybe both. But for me, writing your mind is not interesting unless you have cultivated and groomed a mind that is worth writing. This isnít a very democratic idea. A mind isnít interesting simply because it is one. It gets back to reading and writing and living in a certain way that promotes inner growth. I find thereís always will and choice involved.

BIO: Frank X. Gaspar is the author of two novels: Leaving Pico (Hardscrabble Books 1999), a Barnes and Noble Discovery Award winner, a Borders Book of Distinction, and winner of the California Book Award for First Fiction; and his most recent novel, Stealing Fatima, which is forthcoming this November, 2009. He has published four collections of poetry: The Holyoke, re-issued in 2007, Night of a Thousand Blossoms (Alice James Books, 2004, and named by Library Journal as one of the twelve best poetry collections of the year), A Field Guide to the Heavens (1999 Brittingham Prize) and Mass for the Grace of a Happy Death (1994 Anhinga Prize for Poetry). He is the recipient of numerous awards including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, three Pushcart Prizes, and a California Arts Council Fellowship. His poetry is widely anthologized and appears in Best American Poetry of 1996 and 2000. Born in Provincetown, Massachusetts, he now lives in Southern California and teaches at Long Beach City College.

BIO: Frank X. Gaspar is the author of two novels: Leaving Pico (Hardscrabble Books 1999), a Barnes and Noble Discovery Award winner, a Borders Book of Distinction, and winner of the California Book Award for First Fiction; and his most recent novel, Stealing Fatima, which is forthcoming this November, 2009. He has published four collections of poetry: The Holyoke, re-issued in 2007, Night of a Thousand Blossoms (Alice James Books, 2004, and named by Library Journal as one of the twelve best poetry collections of the year), A Field Guide to the Heavens (1999 Brittingham Prize) and Mass for the Grace of a Happy Death (1994 Anhinga Prize for Poetry). He is the recipient of numerous awards including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, three Pushcart Prizes, and a California Arts Council Fellowship. His poetry is widely anthologized and appears in Best American Poetry of 1996 and 2000. Born in Provincetown, Massachusetts, he now lives in Southern California and teaches at Long Beach City College.

Frank's photo by David A. Lipton